Released Nov. 20, minutes of the October 29, 30 Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting delivered more ‘taper’ talk fodder for the media to obfuscate and ‘spin’ an otherwise straightforward statement regarding guidance to the Fed’s so-called ‘quantitative easing’ program.

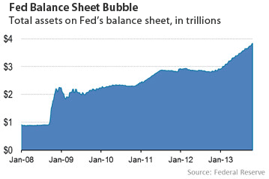

It was on May 22 when Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke’s mentioned the word “taper” as part of his testimony on Capitol Hill, and has become part of the Fed-speak lexicon since, as the Fed now try to lay the difficult groundwork for ending a growing investor perception that it’s creating asset price ‘bubbles’ as a nasty side-effect of its open-market purchases of US Treasuries and Mortgage-back Securities (MBSs).

It was on May 22 when Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke’s mentioned the word “taper” as part of his testimony on Capitol Hill, and has become part of the Fed-speak lexicon since, as the Fed now try to lay the difficult groundwork for ending a growing investor perception that it’s creating asset price ‘bubbles’ as a nasty side-effect of its open-market purchases of US Treasuries and Mortgage-back Securities (MBSs).

Since Bernanke’s May testimony in Washington, bubbles have grown further, still. Record stock prices, a Francis Bacon painting sets a record high price paid at auction of $143 million; the ‘Pink Star’ diamond fetches an unprecedented $83 million; and real estate prices in Malaysia, New Zealand and Canada to luxury homes in Sidney Australia all set fresh record-high prices.

After four months of post-May testimony of Bernanke, expectations-building and drama choreographed around the taper scare by the financial media led to the ‘shocking’ announcement at the close of the Sept. 18 FOMC meeting that the Fed will not taper its monthly purchases of $85 billion of debt securities.

The announcement unleashed a collective sigh of relief on Wall Street.

Alas, a false alarm. Everyone back into the pool! The ‘risk-on’ trade is back. The Dow immediately rallied sharply, rising 200 points from the day’s low, also sending gold much higher still by more than $50 per ounce following the announcement.

While the media hyped an imminent change to the Fed’s five-year-long quantitative easing program during that four-month period, the few skeptics who rightfully pointed out the conditional fine print necessary to trigger a cutback in the Fed’s purchases were outnumbered and out-voiced. The power of the media drowned out the deserting voices.

“[C]hairman [Bernanke] never said that we were going to reduce the rate of asset purchases in September,” head of the NY Fed, William Dudley, rightful points out in a Sept. 24 CNBC interview with Steve Liesman. Adding, “He said ‘later this year.’ I think that framework that he laid out is still very much intact.”

But when Liesman asks Dudley whether the Fed will actually begin to taper this year, Dudley backpedals, saying, “I certainly wouldn’t want to rule it out. But it depends on the data.” [emphases added]

Find exhibit A, below, the section of the Oct. 29, 30 FOMC minutes that’s got the media selling the investing public the notion of a Fed plan to slowdown its purchases of debt securities is just around the corner.

Exhibit A – Portion of Oct. 29, 30 FOMC meeting minutes

“During this general discussion of policy strategy and tactics, participants reviewed issues specific to the Committee’s asset purchase program. They generally expected that the data would prove consistent with the Committee’s outlook for ongoing improvement in labor market conditions and would thus warrant trimming the pace of purchases in coming months. However, participants also considered scenarios under which it might, at some stage, be appropriate to begin to wind down the program before an unambiguous further improvement in the outlook was apparent. A couple of participants thought it premature to focus on this latter eventuality, observing that the purchase program had been effective and that more time was needed to assess the outlook for the labor market and inflation; moreover, international comparisons suggested that the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet retained ample capacity relative to the scale of the U.S. economy. Nonetheless, some participants noted that, if the Committee were going to contemplate cutting purchases in the future based on criteria other than improvement in the labor market outlook, such as concerns about the efficacy or costs of further asset purchases, it would need to communicate effectively about those other criteria. In those circumstances, it might well be appropriate to offset the effects of reduced purchases by undertaking alternative actions to provide accommodation at the same time.” [emphasis added]

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Phrases such as “might, at some stage”, “more time is needed” and merely “contemplating cutting purchases” don’t read like a plan, at all. Essentially, the Fed’s October FOMC meeting minutes read more like an old Publishers Clearinghouse you-may-have-already-won sales pitch letter than any serious communique of an intent to taper the Fed’s debt securities purchases.

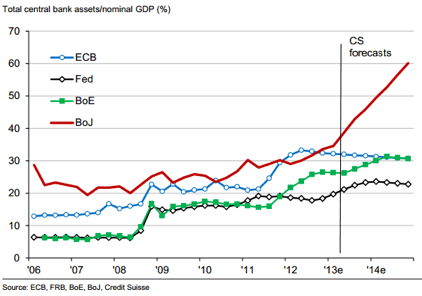

In fact, the verbose posturing of a taper in the first half of the paragraph is totally negated by the line: “moreover, international comparisons suggested that the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet retained ample capacity relative to the scale of the U.S. economy,” which, when translated, means: compared with other nations, the Fed’s balance sheet, as a percentage of GDP, is smaller. See exhibit B, below.

Therefore, in the Fed’s way of thinking, further balance sheet expansion may come with no harm in the Forex against its rival currencies, the euro, yen and pound, a theory expressed by Bernanke in prior communiques.

Exhibit B – Total central bank assets/nominal GDP (%)

However, if the Fed seeks to slow its bulging balance sheet as the data begin to show an improvement toward a fully recovered economy, the evidence overwhelmingly suggests the Fed won’t be tapering anytime soon.

Starting with unemployment, the overall data landscape looks quite bleak.

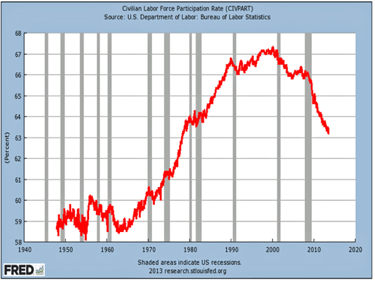

Removing the debate whether the narrower measure of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) unemployment rate (U-3) is a better assessment of the employment landscape in America than the broader measure of unemployment (U-6), a more reasonable metric (exhibit C), the labor force participation rate, better captures the state of the US job market. There, especially, the picture appears dire.

Exhibit C – Labor force participation rate

From exhibit C, above, the participation rate continues to drop, and now appears to match the job market participation rate of the economic rough times of 1978-9. Note that the participation rate peeked some time during the top of the Nasdaq bubble and has steadily deteriorated, thereafter.

Source: U.S. Department of Labor

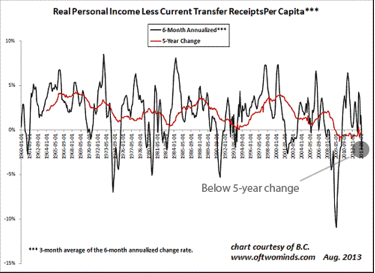

Personal incomes, another important measurement used to forecast future total output, weighs heavily in an economy dependent upon approximately 70% of its GDP derived from consumer spending.

The graph, below, exhibit D, comes courtesy of OfTwoMinds blog.

Source: OfTwoMinds.com

“There are two noteworthy points in this chart,” explains Charles Hugh-Smith of OfTwoMinds blog. “One is that real personal income has been negative for the past five years, with one tax-related spike in late 2012 as those who could do so reported income in 2012 rather than 2013 to take advantage of the lower tax rates that expired in 2012.”

He adds, “The second point is that every time the black line (the 6-month annualized rate of change) of real personal income fell below 0% (that is, went negative), a recession occurred.”

He adds, “The second point is that every time the black line (the 6-month annualized rate of change) of real personal income fell below 0% (that is, went negative), a recession occurred.”

Now, let’s look at corporate earnings, a predictor of an employer’s proclivity and ability to hire more full-time workers.

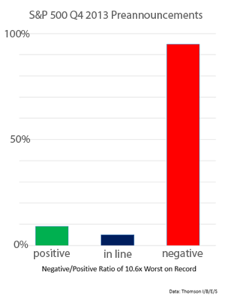

There, the most recent guidance from companies which make up the S&P500 don’t look any better than employment or personal income trends.

Of the companies which make up the S&P500, approximately 90% has issued negative guidance regarding earnings, according to Thompson I/B/E/S.

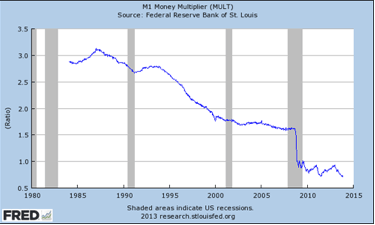

And, finally, the exhibit which must scare the Fed the most, and, by itself, foretells a highly unlikely scenario in which the Fed would taper while this measure drops like a stone in the ocean; it’s the money multiplier statistic calculated by the Fed to assess levels of credit expansion within the economy.

Exhibit E – M1 Money Multiplier

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

According to the exhibit E, money entering the banking system isn’t multiplying by way of subsequent new loans issued via a system of fractional banking. In other words, business and consumers don’t have enough disposable income or confidence in future income prospects to increase debt levels.

Conclusion

In short, given the components of GDP, where GDP = private consumption + gross investment + government spending + (exports − imports), or GDP = C+I+G+(X-M), weak private consumption, weak capital expenditures and a trade deficit leave only government spending to replace the weak components.

And while there appears to be no political will in Washington to drastically cut spending, the Fed must accommodate Treasury’s need to fund itself.

The two top creditors, China and Japan, have not kept pace with the rate of increase to the accumulating federal debt of $17 trillion (cash accounting). Therefore, the slack in demand requires another buyer to pick up the marginal drop in overseas purchases of US debt. That buyer must be the Federal Reserve, typically referred to as the lender of last resort. But, today, in this case, the Fed is now the buyer of last resort.

There will be no taper.

0 Comments